In the aftermath of the school shooting at Annunciation Catholic School in Minneapolis on August 27, I came across a random post on LinkedIn in which the author said, “I guess school shootings are routine now.” I responded that they were not, based on the evidence posted below. I was doing a quick search of the Interwebs to make sure, and I found some pretty startling things. Chief among them was that there are incidents in schools that are identified as school shootings that do not actually involve shootings. That begs the eponymous question: What is a school shooting?

An advocacy group, Everytown for Gun Safety says, “Everytown tracks every time a firearm discharges a live round inside or into a school building or on or onto a school campus or grounds, as documented by the press.” The K12 School Shooting Database, created by David Reidman, defines a school shool shooting as, “A gun is brandished, is fired, or a bullet hits school property for any reason, regardless of the number of victims (including zero), time, day of the week, or reason.”

The Gun Violence Archive is an independent reasearch and data collection non-profit organization that tracks incidents of gun violence. On their website, the Gun Violence Archive defines a school shooting as, “an incident that occurs on property of the elementary, secondary or college campus where there is a death or injury from gunfire. That includes school proper, playgrounds, “skirt” of the facility which includes sidewalks, stadiums, parking lots. The defining characteristic is time…Incidents occur when students, staff, faculty are present at the facility for school or extracurricular activities. Not included are incidents at businesses across the street, meetings at parking lots at off hours.”

The CDC does not have a definition for ‘school shootings’ but does track “school-associated violent deaths“. This defintion is, “A homicide, suicide, or legal intervention in which the fatal injury occurred 1) on the campus of a functioning public or private elementary or secondary school in the United States, 2) while the victim was on the way to or from regular sessions at such a school, or 3) while the victim was attending or traveling to or from an official school-sponsored event.”

The list could go on, but already there are four different definitions from four different groups. Why the vast differences? One of the reasons might be the agenda of the organization. Everytown is a gun control advocacy group. David Reidman and the Gun Violence Archive conducts research. The CDC is a government organization. Each has a reason for doing what they do. Those reasons guide their approaches, and has the potential to warp their results. As readers, we need to be aware of the writer’s agenda, and keep it in mind as we read.

I am happy to share my agenda. I have been actively involved in school safety since 2002, when a tornado gave my elementary school a glancing blow. I became an Indiana School Safety Specialist in 2004. I learned that school safety should be data-driven, and hazards-based. That means schools, which have limited resources, should be creating safety plans for those things that are likely to happen at their school, which are identified during a risk asssessment. It should be common sense. Let’s say I do a risk assessment for my school and identify a risk, labeled X. A vendor comes to me and demonstrates a program that addresses a different risk, labeled Y. Why would my school pay for Y, when it’s not addressing my identified risk X?

In 2014, I conducted an observational study called Relative Risks of Death in K12 Schools, published by Safe Havens International, the world’s largest non-profit school safety center. I used national data specific to K12 public schools in the US, which covered 1998, a year before the Columbine attack, to 2012, a 15-year period. During that period the greatest number of fatalities occurred in school transportation-related incidents, with 525 fatalities. During the same time period, there were 489 school-related homicides and 112 school-related suicides.

For most people, when they think of school shootings, they think of a person with a gun who is hunting targets in the school. This is referred to as an Active Shooter Incident, or ASI. The US Department of Homeland Security(DHS) defined an ASI as, “An individual actively engaged in killing or attempting to kill people in a confined and populated area; in most cases, active shooters use firearms(s) and there is no pattern or method to their selection of victims.” Examples of this are the Columbine, Sandy Hook and Parkland attacks. The study noted there were 22 ASIs in public schools, with 62 fatalities.

We’ve arrived at the point in the conversation I hate, because it should be obvious: Any child lost is a tragedy. Boiling this down to the numbers isn’t about forgetting that. If anything, efficiently applying a school’s limited resources to address threats they are likely to face, instead of wasting those resources on products or services that won’t is about saving children’s lives.

Do children bring guns to schools at other times than ASIs? Absolutely. Students are killed in gang-related incidents, accidental discharges, interpersonal disputes, etc. Schools, however, have different plans to mitigate, respond to, and recover from such incidents that are vastly different than for ASIs. There are programs schools can use to address gang issues, interpersonal disputes and suicide prevention.

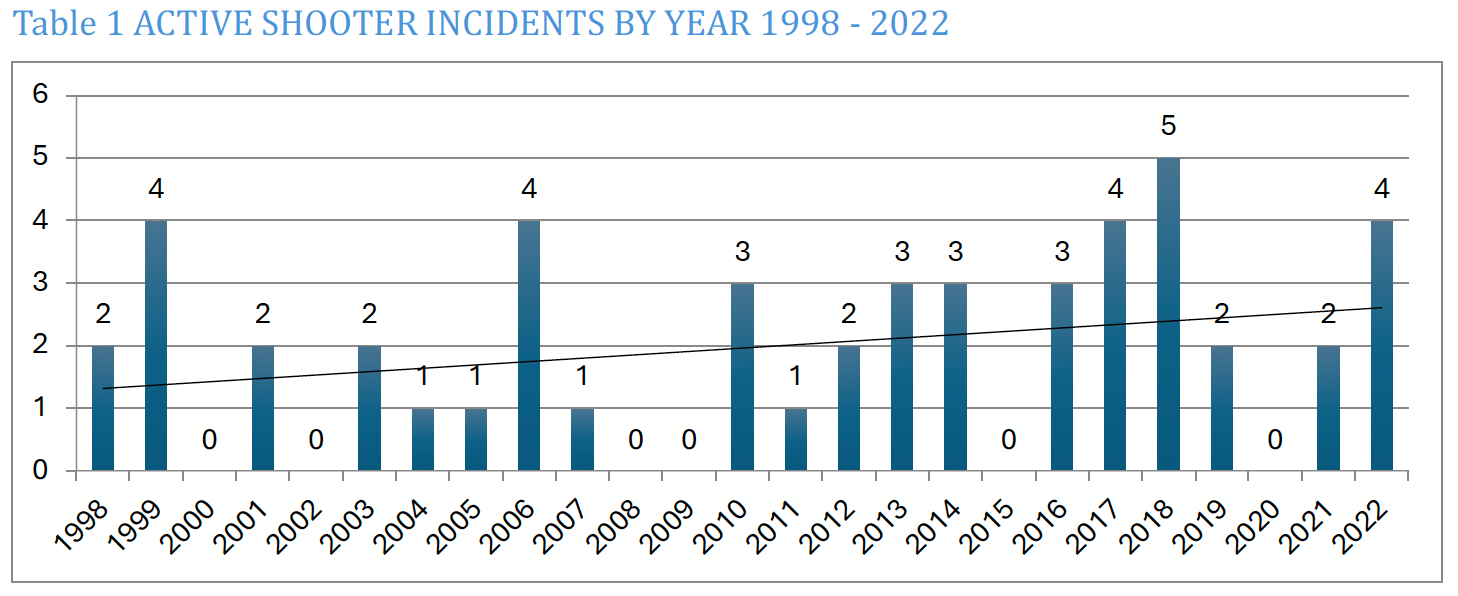

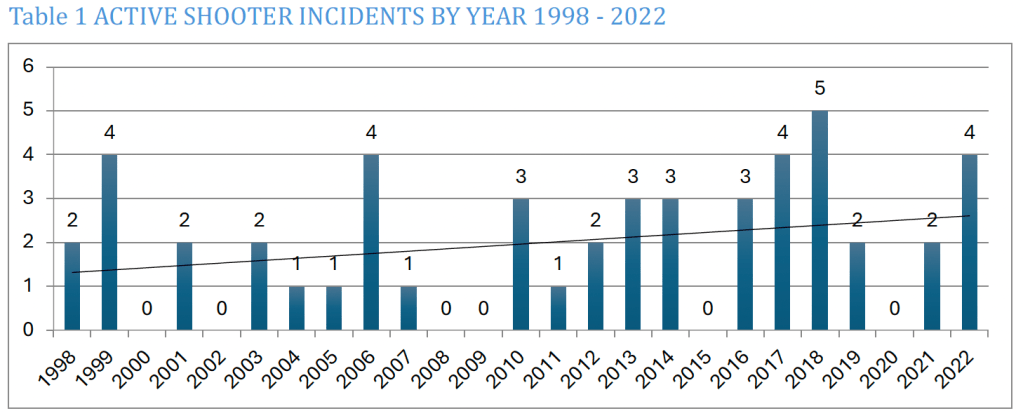

Take a look at the table below. I am in the process of updating the 2014 study to cover a 25-year period from 1998-2022. The graphic shows a total of 49 ASIs in that 25 years. The thin black trend-line running from left to right in the graph shows a slight increase in the number of ASIs. The original study had a horizontal trend line, indicating that ASIs were not increasing as of 2014. Of note is that six years did not have a single ASI.

A black swan event is an unpredictable and rare event with a culture-wide, paradigm-shifting impact. ASIs are often such events. Columbine caused major changes to law enforcement and schools around the US. Sandy Hook taught us that these types of events are meticulously planned. Uvalde shocked us with the inaction of the police. I don’t think, however, that we’ve reached the point where they are ‘routine’.

Gun violence is a societal problem and, like other societal problems, can often make its way into schools. Schools need to conduct comprehensive risk assessments and identify the specific risks for which they need to prepare. Parents need to hold their schools, and school leaders, accountable for the safety of their children. We, as a society, need to ensure that these black swan events never become routine. Our kids deserve it.