Mark Levin is an icon in conservative circles. He worked in the Reagan Administration as the Chief of Staff for Attorney General Ed Meese. He is a constitutional attorney, and was close friends with Rush Limbaugh. That is how I first heard of him, listening to Rush and his friend “F. Lee Levin”. He has his own show, The Mark Levin Show, where he is combative, brash, and usually right.

He is a prolific writer. The first book of his I read was Men in Black, a 2005 treatise on the US Supreme Court. I loved that book. I learned so much about the Supreme Court, and why it’s important to have originalist justices. Many of his books have been #1 on the New York Times Best Seller’s List. His tenth book is On Power. What I hope to do is the same as I did for Identifying Child Molesters, by Carla van Dam. I will share with you what I learn from this book, chapter by chapter. Today’s entry is Chapter One-On Power.

The first chapter of the book examines power, and begins to define the term. It’s a difficult thing to do, because the context, and the circumstance, is important. He links power to liberty describing too much liberty, or anarchy, as well as too little liberty, or tyranny. The linkage depends on who exercises power, how much power is exercised, and whether the exercise is bound by human rights.

The American Revolution is given as an example of the proper application of power. The purpose of the revolution was to promote individual and societal liberty through a representative, limited, and divided government. He describes this as ordered liberty, which autocrats seek to subvert by limiting the liberty of others to increase their own power. He writes that this is the paradox that has destroyed democracies throughout world history. Centralization of power leads to reduced individual and societal liberty.

Centralization is the theme for the rest of the chapter. Levin introduces the reader to one of the themes of the book, the use of language in the application of power. For example, the words liberty and democracy are used by people who seek to restrict personal liberty through the centralization of power. He quotes Abraham Lincoln, “We all declare for liberty,” said Lincoln, “but in using the same word we do not all mean the same thing. With some the word liberty may mean for each man to do as he pleases with himself, the the product of his labor; while with others, the same word may mean for some men to do as they please with other men, the product of other men’s labors.”(page 4) Lincoln says that while each is called liberty, they are two, incompatible things called liberty and tyranny.

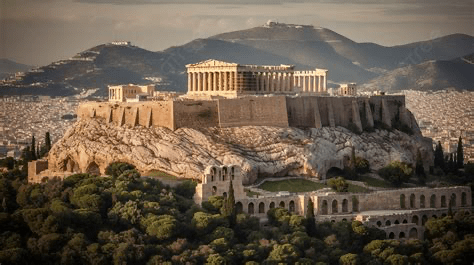

The same is true for the word democracy. I have lost count of how often some politician or pundit talks about our “sacred democracy.” They often do this while discussing patently undemocratic governmental actions. My stock response is that we are a constitutional republic. We should understand that the ancient democracy of Athens only survived about fifty years. It collapsed under the anarchy brought about by its unfettered democracy.

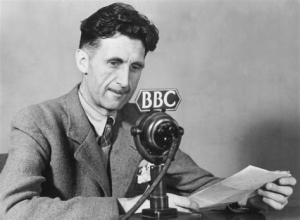

George Orwell wrote about the perversion of “political words… used in a consciously dishonest way. That is, the person who uses them has his own private definition but allows his hearer to think he means something quite different.” He goes on to write, “It is almost universally felt that when we call a country democratic, we are praising it: consequently, the defenders of every kind of regime claim that it is a democracy, and fear that they may have to stop using the word if it were tied down to any one meaning.”(page 5)

I learned a new piece of information. Seventy percent of the world’s population lives under an autocratic regime (page 6). Mark asks an important question: Is this the natural state of man, at least in the communal sense? It’s here that Mark introduces one of two main terms in his book, negative power.

“In a democracy,” Mark writes, “negative power typically takes the form of a steadily increasing centralization of authority that starts slowly but eventually spreads more quickly to cover all corners of the nation, moving closer toward a quasi-autocratic model.” (page 7) He explains that this occurs in three general ways. One way is the imposition by the few, like the judiciary. Another is the peaceful vote of the many. Lastly, there’s the slow institutionalization by a domineering army of bureaucrats.

In contrast, Mark uses the example of the transition from the Articles of Confederation to the US Constitution. He refers to this as positive power. Under the Articles, the federal government could not override states. It lacked the necessary authority to do so. However, the Founders knew this centralization was negative power. This understanding came from The Enlightenment and writers like John Locke and Montesquieu.

Here is the paradox faced by the Founders. The gathering of power through centralization was necessary to prevent the approaching anarchy caused by the Articles of Confederation. Yet, man is imperfect. Giving a few men more power would be corrupting. This corruption can cause anarchy. An excess of liberty can lead to the tyranny of too little liberty. How would they strike the balance? The genius of these men was that they looked to those who went before them. Aristotle, Cicero, and the aforementioned Locke and Montesquieu all wrote about how to centralize power in a government. They also discussed dispersing that power through checks and balances. Mark concludes that “…a positive power structure attempts to contain and control the dark side of the human character and experience and emphasizes the capacity for a civilized, just society.” (page 10)

The Declaration of Independence set forth the ideals of this positive power structure. The US Constitution provided the outline of the form of government that would embody those ideals. It also offered a way to change that outline should the need arise. Montesquieu wrote, “Even virtue has need of limits. So that one cannot abuse power, power must check power by the arrangement of things.” (page 12) Thus, our three branches of government, executive, legislative and judicial, and the checks and balances of each.

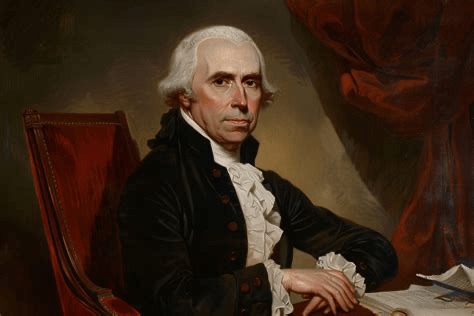

The Father of the Constitution, James Madison, famously wrote in Federalist no. 51, “If men were angels, no government would be necessary. If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary. Framing a government to be administered for men over men is difficult. First, you must enable the government to control the governed. Next, oblige it to control itself.” (page 15)

So Mark has set the table. We will examine how negative and positive power manifest, as well as their impact on our lives. The goal, of course, is to strengthen individual liberty and confront tyranny.